What is the impact of the Covid-19 crisis on gender inequalities in the labour market?

Before the health crisis, the female employment rate had risen steadily for more than 40 years. From an average employment rate, for the female population aged between 15 and 64 years, of 36 % in the 80s, it rose to nearly 62 % in 2019. However, this trend has still not caught up with the male employment rate (69 % in 2019). Could the current crisis lead to a worsening of the position of women in the labour market?

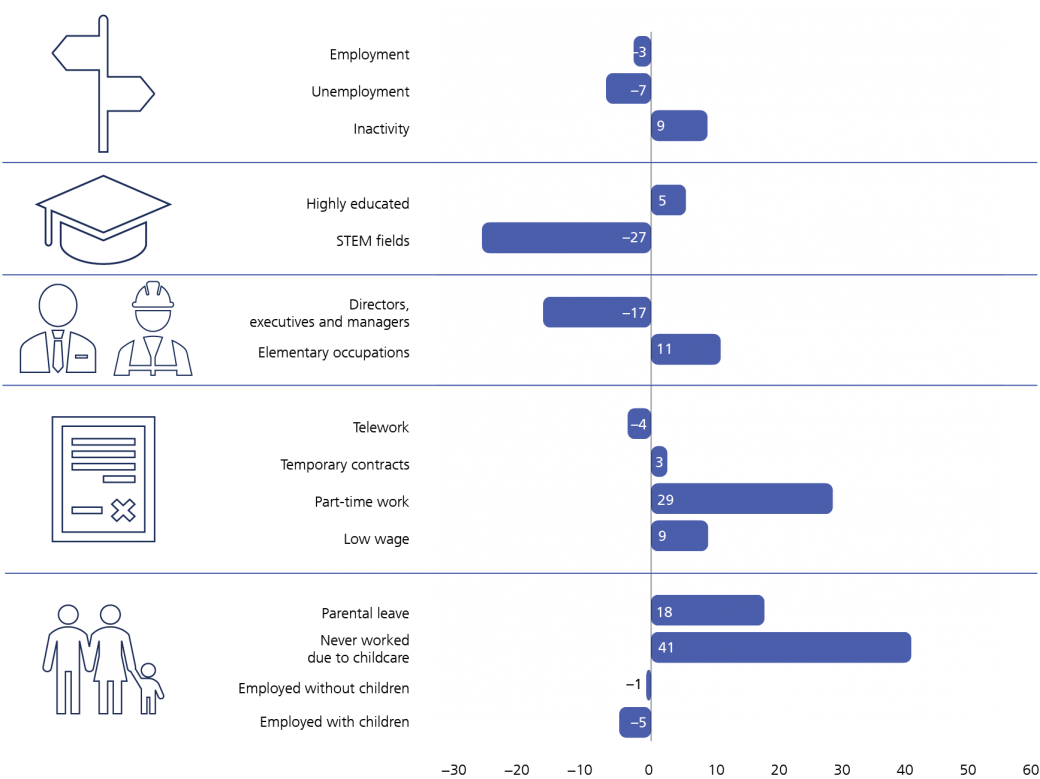

Position of women in the labour market in Belgium

(over- or underrepresentation of women with respect to their share in the population, in percentage points)

Sources: Eurostat, NEO, Statbel.

STEM: Science, technology, engineering and mathematics

Contrary to what we have observed in the past during economic crises, the health crisis has had a stronger impact on the service sectors, with job losses reaching -2.4 % during the first three quarters of 2020 in the other services sector (particularly social care), -6 % in administrative service activities and as much as -7.5 % in food service activities and accommodation. Retail trade also recorded a shrinking of its workforce by 0.8 %. This sector is unusual as it includes shops which are considered non-essential and forced to close as well as essential shops, which have remained open throughout the crisis. The health care sector, in the front line in tackling the health crisis, has also experienced an exceptional surge in activity. All activities in which women are overrepresented compared to their share in aggregate employment. It is also noticeable that wages in these sectors are particularly low, making workers more vulnerable to loss of employment and challenging the enhancement of working conditions for certain occupations.

In addition, more women are employed in the education sector (71 %) and slightly overrepresented compared to their share in total employment in the public sector. These are two sectors in which employment has been preserved and the wage payments maintained.

In view of this, it is difficult to assess the overall impact on female employment at present.

Temporary unemployment data reveals a higher proportion of men among the beneficiaries, throughout the crisis. As far as unemployed job-seekers are concerned, there is also a stronger rise for men (+5 %) than for women (+2 %). Despite this, compared to the economic and financial crisis, female contribution to rising unemployment is greater in the midst of the health crisis. While women accounted for only 22 % of the increase in job-seekers recorded in 2009, they represent 35% of the rise observed since the start of the health crisis.

Even though women are increasingly active in the labour market, most domestic tasks still fall to them. In 2016, 89 % of women looked after children daily in Belgium, compared to 75 % of men. The differences are even more marked for housework as 81 % of women cook or do housework every day, while the same applies to just 33 % of men. Women are also much more likely to reduce their working hours or take career breaks to raise children. 51% of them do so, compared to just 7 % of men.

The health crisis has amplified this imbalance in the sharing of roles as women have taken on the majority of the extra domestic work, particularly in terms of childcare, due to the closure of schools and nurseries during the first lockdown. This is reflected in the data from the National Employment Office on coronavirus-related parental leave, 71 % of which was taken by women (compared to 68 % on average in 2019 for ‘normal’ parental leave). Nevertheless, the short-term impact of outflows from the labour market or reductions in working hours could persist, in view of the importance placed on work experience. The mothers involved could find themselves with less promising career prospects and lower wages than they could have attained without these constraints.

A study by the European Parliament conducted in September 2020[1] sounds a more positive note. This reveals that, during the lockdown, men also spent more time on housework and childcare, although this increase was still below that for women. Hopefully, this new role taken on by fathers might change how families and employers view fatherhood and lead to a permanent change of attitude. This should have an even greater impact in families where the load was transferred from the woman to the man, such as where the mother worked in an essential sector and the father not.

In sectors which have managed to roll this out on a large scale, widespread working from home during the crisis and the greater flexibility this will doubtless bring in future in the management of working hours and location could represent an advantage for women. It is still too early to know for sure, but teleworking could allow women to juggle career and parenthood more easily by preventing them from having to opt to reduce their working hours. Due to the composition of employment, we see a higher proportion of men among those working from home. However, with the health crisis, women’s access to teleworking has risen sharply: in November 2020, according to the data from the labour force survey, nearly 42 % of them worked from home, compared to 37 % of men. Despite the positive aspects involved (flexibility, less commuting), teleworking could also pose a risk for working women since they will be perceived as being more available to carry out housework and child rearing. Within their household, this could heighten the imbalance in the sharing of tasks. In work, women could be perceived as less invested in their jobs, with repercussions in terms of career and wage. Working from home should therefore not supplant an accessible and affordable childcare system or the possibility of flexible working hours.

This brief review of the consequences of the health crisis for female employment demonstrates the complexity of the situation of women in the labour market. This requires in-depth research, particularly into the type of jobs they hold as well as work-life balance, since women appear to be the main adjustable variable within households. With the aim of contributing to the public debate on the subject and performing a scientific analysis, the Bank will undertake a study on “The impact of parenthood on the careers of women and men”, the results of which will be published in the Economic Review for December 2021.

Key takeaways:

- Greater risk of job loss than during the financial crisis

- Overrepresentation in the health care sector, in the front line in tackling Covid-19. Opportunity to boost their wages?

- More career breaks and reduced working hours than for men in general and especially during the crisis. Risk to career prospects

- Greater involvement of fathers in childcare (although still proportionally less than for mothers) during the first lockdown. Opportunity for a change of attitude or short-term effect?

- Increased recourse to teleworking for women during the crisis. Opportunity for a better work-life balance or greater psychosocial risks?

[1] The gendered impact of the COVID-19 crisis and post-crisis period (europa.eu)