Higher interest rates on reserves held at the central bank: a boon for banks?

This blog post explains how these large reserves arose and how the interest paid by the central bank on these deposits allows monetary policy to be tightened. The fact that this remuneration is in line with market interest rates – and even steers market rates – means that they are not a bonanza for banks. However, as these reserves have a maturity of one day, the higher the share of reserves held at the central bank on the banking sector’s balance sheet, the quicker its interest income reacts to rate changes. This lower exposure to interest rate risk, in turn, gives banks more leeway to grant long-term loans. This support for bank lending was in fact one of the transmission channels for the asset purchase programmes introduced when inflation was low.

Why do banks have such large reserves at the central bank today?

During previous cycles of interest rate hikes, such as those seen in 1999-2001 and 2005-2008, banks held only required reserves at the central bank: there was no excess liquidity. Interest payments by the central bank to commercial banks were therefore limited. Today, however, reserves held at the central bank, de facto overnight deposits, account for a substantial share of the assets on banks’ balance sheets. This can be explained by two monetary policy measures adopted when inflation was low.

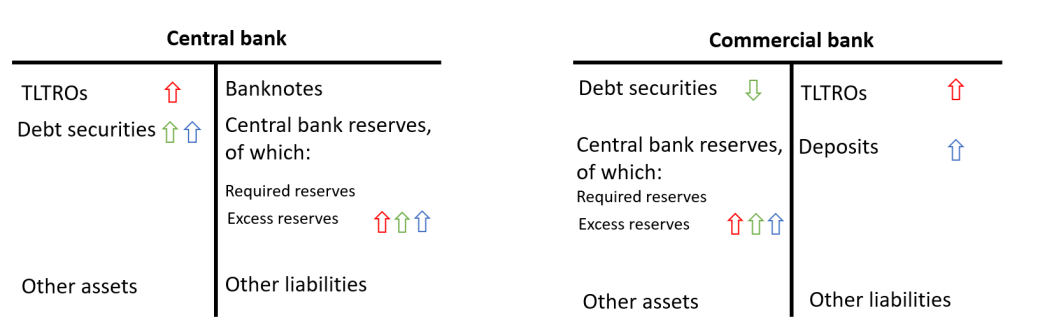

First, commercial banks were able to borrow from the central bank at attractive terms and for long periods in the form of TLTROs (targeted longer-term refinancing operations). These transactions encouraged banks to maintain or even increase their lending to households and businesses. The counterpart on the assets side of the balance sheet to this item on the liabilities side is reserves held at the central bank (the red arrows in the figure below). Until recently, these reserves represented a major source of excess liquidity, but they have been decreasing steadily since the end of 2022 due to large repayments of TLTROs. On the other hand, bond purchases by the central bank, the second monetary policy measure, tend to have a longer-lasting impact on excess liquidity in the euro area banking sector. This is due to the fact that the bonds purchased have a remaining term to maturity of several years.

The central bank buys bonds (debt securities) through a commercial bank and pays for them with new reserves. When a commercial bank sells bonds in its portfolio, the composition of its assets changes: the bonds, with a longer maturity, are replaced with a sight deposit with the central bank (green arrows). When the central bank buys bonds held by other market actors, for example a pension fund, a commercial bank acts as an intermediary in the transaction as only such banks can be counterparties in monetary policy operations. The end result is a bigger balance sheet for banks with, on the assets side, additional reserves held at the central bank and, on the liabilities side, a debt to, in our example, a pension fund in the form of a deposit (blue arrows).

Why is the interest rate paid on these reserves important?

When there is excess liquidity in the banking system, the interest rate paid on reserves held at the central bank determines the monetary policy stance. This interest rate, the so-called deposit facility rate or DFR, is currently the most important policy rate[1] as it drives other interest rates in the capital markets. As banks know that they can deposit excess liquidity with the central bank at this rate, it serves to anchor other interest rates in the financial markets.[2]

The interest rate on reserves held at the central bank serves to anchor other interest rates in the financial markets.

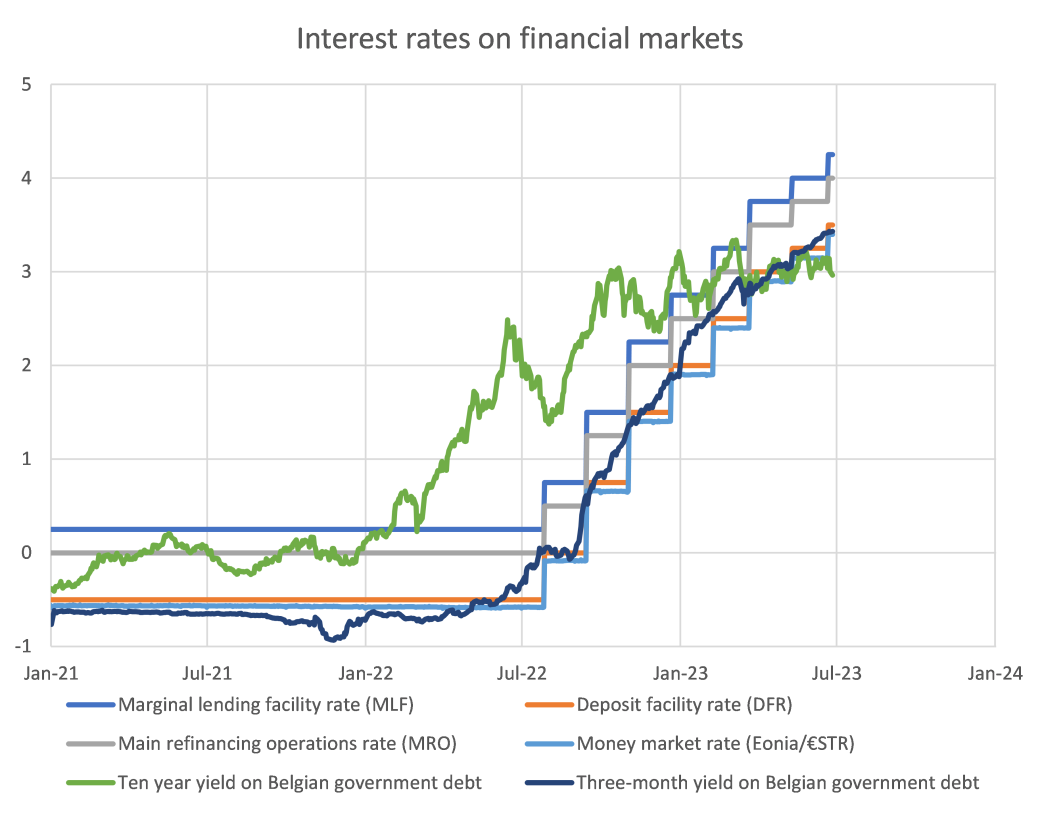

When inflation was low, the deposit facility rate was negative and led to many other capital market interest rates also entering negative territory. Even government bonds with long maturities had negative yields. These negative interest rates helped shore up consumption and investment and thus counteract the low inflation rate.

During the post-pandemic economic recovery, inflation reached a worryingly high level and in December 2021, the ECB began to tighten its monetary policy stance. After stopping additional asset purchases, it began raising its policy rates in July 2022. It has since raised them by 400 basis points in total: the deposit facility rate was -0.5% in June 2022 and stood at 3.5% in early July 2023.

In the wake of these rate hikes, other financial market interest rates also rose. This was precisely the ECB’s objective: higher policy rates are a means of achieving tighter financing conditions throughout the economy. In this way, it is possible to avoid overheating, namely a situation in which consumption and investment are too dynamic and prevent inflation from returning to the 2% target. Short-term interest rates, such as those on short-term government securities or the money market in the broad sense, reflect the rate hikes most clearly. On the other hand, long-term interest rates, such as on 10-year government bonds, are less anchored to current policy rates. This is because they are driven more by expectations as to the future path of these rates than by past rate hikes.

Higher policy rates are simply a means used by the ECB to achieve tighter financing conditions throughout the economy.

Is the interest paid on these reserves a bonanza for banks?

Both in the press and in economic circles, there is much discussion suggesting that the interest payments banks receive on their overnight deposits with the central bank are in fact a risk-free subsidy from the latter. The reality is more nuanced, however.

The impact of tighter monetary policy on banks’ interest income depends on the level of reserves held with the central bank. The interest rate paid on these reserves is not a decisive factor in this regard: banks receive remuneration in line with market rates, namely the short-term risk-free rate. Thus, with regard to remuneration, these reserves do not constitute a boon for banks: the end result, in terms of the applicable rate, would be the same if they were to hold, for example, short-term government securities. In that case, the Treasury would be granting the alleged “subsidy” to banks.

That being said, the fact that reserves held with the central bank have a maturity of one day and thus benefit immediately from a higher deposit facility rate in their entirety is a decisive factor. If a bank has more reserves with the central bank than long-term debt securities on its balance sheet, this pushes down the average maturity of its assets and causes its interest income to react more quickly to interest rate changes. In this situation, interest income rises immediately when monetary policy is tightened (i.e. rates are raised), while a bank with more long-term assets will only benefit from higher rates with some delay. In other words, banks with more short-term assets are less exposed to interest rate risk. Interest rate risk refers to foregone interest income in the event of a rate hike or, similarly, a loss in value on long-term securities.

Moreover, the reduction of interest rate risk in the banking sector was one of the transmission channels for the asset purchase programmes introduced by the ECB when inflation was low. Indeed, this gave banks room to take on new interest rate risk, provide long-term loans and support investment. The dynamic growth in long-term fixed-rate mortgage loans seen in recent years is evidence to this effect. This choice by banks caused their interest rate risk to rise again or, in other words, made their earnings less sensitive to interest rate changes.

In short, reserves held with the central bank are appealing to banks not because they constitute a bonanza but rather because they help protect their bottom line against interest rate risk.

In conclusion, reserves held with the central bank are appealing to banks not because they constitute a bonanza but rather because they help protect their bottom line against interest rate risk.

Footnotes

[1] The other policy rates are the marginal lending facility (MLF) rate, or the interest rate banks pay when they borrow overnight (against collateral) in the event of an unexpected shock, and the main refinancing operations (MRO) rate, or the rate at which banks can borrow for one week (against collateral). Due to excess liquidity, these interest rates do not currently determine the course of monetary policy.

[2] As certain assets are highly coveted and not all financial institutions with substantial liquidity have access to the central bank, the real picture is more nuanced: some interest rates in the money and capital markets are currently slightly lower than 3.5%, the deposit facility rate in early July 2023.