What are “greedy jobs” and why do women avoid them?

Claudia Goldin was born in New York City in 1946. She first dreamed of becoming an archaeologist, then a microbiologist, before discovering economics under the tutelage of Professor Alfred E. Kahn at Cornell University. In 1972, she obtained her doctorate in economics from the University of Chicago, and in 1990 she became the first female tenured professor in the economics department at Harvard University.

The research she has carried out over the course of her long career covers a wide range of subjects, from slavery and education to the Great Depression and regulation. However, she is best known for her work on women in the American economy, for which she has now been awarded a Nobel Prize.[1] She becomes only the third woman to receive what is undoubtedly the most prestigious accolade in the field of economics - after Elinor Ostrom in 2009 and Esther Duflo in 2019 - and the first without a male co-laureate. Her work is notable for its innovative nature and multidisciplinary approach, drawing on economics, history, sociology, politics and technological developments.

It’s not the economy!

In her first book, Understanding the Gender Gap: An Economic History of American Women, published in 1990, Claudia Goldin traced the development of female employment in the United States over the course of two centuries. She demonstrated that women's participation in paid employment is not directly linked to the economic cycle, as some had thought, but rather depends on more structural factors such as:

- legislation,

- the level of education and choice of subjects studied,

- changing societal expectations and norms, and

- the development of contraception.

Women's participation in paid employment is not directly linked to the economic cycle, as some had thought, but rather depends on more structural factors.

The book also explained how women had been working more than official statistics may have indicated. Registered simply as a “wife”, many married women in work were not counted in official employment data. On this basis, Goldin recalculated women’s employment rate and demonstrated that it had followed a U-shaped trajectory over the two-hundred-year period. In the agrarian society of the late eighteenth-century, the proportion of married women in paid work reached 60% in the United States. However, industrialisation changed this reality in the 19th century, making it harder for women to work at home: by the beginning of the 1900s, the female employment rate had fallen to 10%. In the twentieth century, more specifically in the post-war period, opportunities for women to work gradually increased again, but the gender imbalance in employment remained substantial.

The gender pay gap is mainly due to parenthood

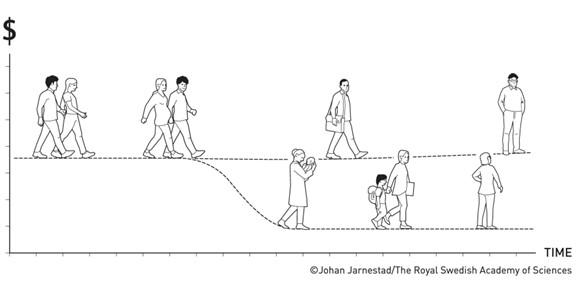

Professor Goldin has closely studied gender pay differences. On the basis of US data, she has shown that, for women and men with similar skills and experience, pay differences are very small at the start of their careers and that the pay gap remains narrow for the first few years of employment. Things change significantly, however, when a child arrives.

In her latest book Career and Family, published in 2021, Professor Goldin highlights that while the gender pay gap between university graduates is smaller today than it was in the past, it unquestionably persists. This is linked to discrimination but also, more insidiously, to societal expectations that women, more so than men, bear responsibility for childcare and the home. Women are typically penalised by the existence of many “greedy jobs”, as Professor Goldin calls them, meaning demanding jobs for which the hourly wage increases with the number or type of hours worked (evenings, weekends, holidays), precisely because they are expected to handle the bulk of domestic duties.

Women are typically penalised by the existence of many “greedy jobs”, as Professor Goldin calls them, meaning demanding jobs for which the hourly wage increases with the number or type of hours worked (evenings, weekends, holidays) precisely because women bear responsibility for the bulk of domestic duties.

Including in Belgium

While Belgium has one of the narrowest gender pay gaps of any OECD country, women’s participation in the labour market remains challenging. The NBB has been studying this issue for several years. A study published in 2021 (Nautet & Piton) shows that, in Belgium, too, leaving one's job or reducing working time following the birth of a first child is a decision predominantly taken by women. Such choices, whether made voluntarily or not, subsequently have significant implications for career development.

While Belgium has one of the narrowest gender pay gaps of any OECD country, women’s participation in the labour market remains problematic. The NBB has been studying this issue for several years.

Analysis of these issues is all the more important given that Belgium has set itself the target of halving the gender gap in employment rates by 2030. NBB economists have carried out an in-depth analysis of factors behind the lower participation of women in the labour market (Conseil Supérieur de l'Emploi, 2023) and issued several recommendations to improve the situation:

- the introduction of mandatory parental leave, to be shared equally between parents, so as to ensure a better distribution of unpaid household tasks between them;

- improvements to the childcare system for pre-school-age children;

- adjustments to the organisation of the school day to provide children with structured activities until the end of their parents’ working day; and

- the encouragement of transparency in criteria for remuneration, recruitment and promotion.

A strong signal

The award of the 2023 Nobel Prize in Economics to Claudia Goldin sends a strong signal. In particular, it demonstrates the importance of understanding the factors that influence women’s participation in the labour market and the need to take these factors into account when developing and implementing public policies. Strengthening gender equality will also require a more equitable sharing of domestic tasks, particularly those relating to children.

Thanks to Professor Goldin’s work, greater attention is being paid to questions of equity, particularly gender equity, by the institutions responsible for macroeconomic stability, such as the NBB. Her Nobel Prize provides a strong incentive to continue this work.

[1] The prize is formally known as “The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel”.