The Belgian economy is gradually recovering after the huge COVID-19 hit but the budget deficit remains unsustainably high

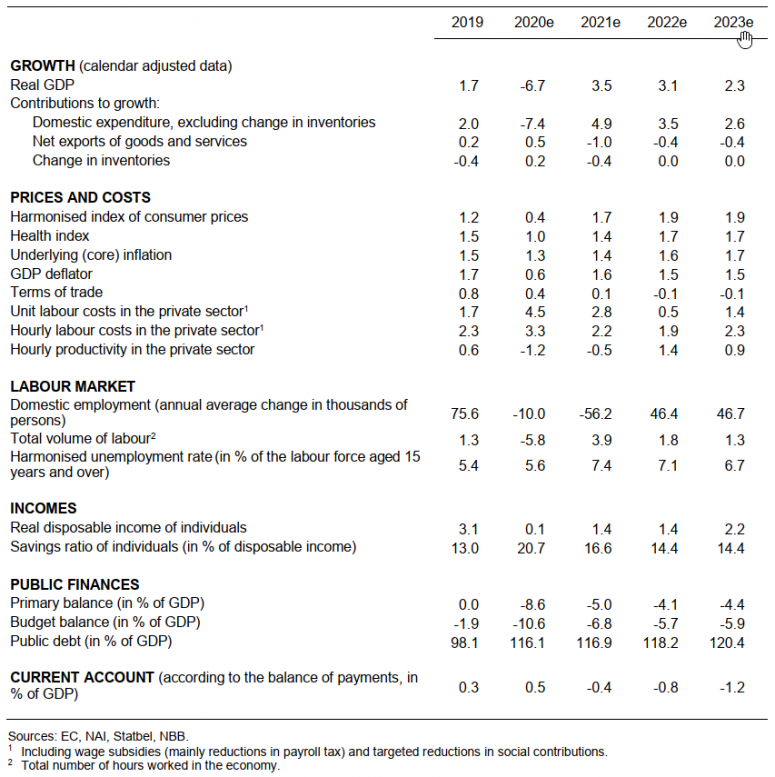

Economic activity in Belgium is set to contract by 6.7 % this year, owing to the restrictive measures imposed to combat the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. The downturn is less severe than initially feared, but it is nevertheless more than three times worse than during the 2008-2009 global financial crisis. As the containment measures are relaxed once again and assuming that an effective medical solution, such as a vaccine against the virus, can be confirmed and rolled out as of next year, a gradual recovery of more than 3 % should be observed over the following two years, driven mainly by household consumption. On the other hand, the recovery of business investment will take a bit longer and net exports will continue to weigh on growth over the entire projection period. The coronavirus crisis also has an impact on the labour market: around 100 000 jobs will have been lost by autumn 2021. The government deficit will rise to more than 10 % of GDP in 2020 and, even more importantly, it will also remain structurally high thereafter, at more than twice the level that would have been reached with no crisis.

Following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, health measures were adopted across the globe in a bid to stop the virus from spreading. Consequently, both global GDP and international trade fell back sharply in the first half of 2020, albeit to a lesser extent that had initially been feared. The relaxation of the measures over the summer allowed for a vigorous upturn, which in most cases nevertheless turned out to be incomplete and short-lived.

Belgium also saw an economic revival in the third quarter, but according to short-term indicators, it quickly ran out of steam, before being snuffed out altogether in the fall by a new COVID-19 wave and the ensuing protective measures. Surveys suggest the impact of the second lockdown on private sector output in the fourth quarter is clearly more limited than in the spring. All in all, economic activity is set to contract by 6.7 % this year.

Assuming that a medical solution, such as an effective vaccine, can be rolled out as of next year, there is likely to be a gradual recovery of more than 3% in the following two years. The recovery will come with both upside and downside risks, largely depending on how the health crisis pans out and whether there are any extra restrictive measures. GDP should have caught up with its pre-crisis level again by the end of 2022, after which growth rates are expected to moderate and settle at 2.3% in 2023.

The economic upturn is primarily driven by household consumption, which is expected to pick up again as the restrictions are relaxed, just as it did after the first lockdown. Besides pent-up demand and a swift return to normal saving behaviour, consumption is also being shored up structurally by the trend in purchasing power. At the height of the crisis, households’ loss of income was limited thanks to massive support measures, such as the temporary unemployment scheme. Moreover, over the 2021-2023 period, per capita purchasing power should pick up again, by 4 % in cumulative terms.

Business investment was cut by a quarter in the first half of the year and is likely to prove harder to revive than household consumption. Continued uncertainty about the recovery of demand, compounded in the short term by the possibility of a no-deal Brexit, is leading firms to postpone their investment projects for a bit longer, or even scrap them altogether. In addition, the contribution of net exports to growth is still negative: imports are expected to pick up more vigorously than exports, notably with the gradual return to normal tourism flows.

In the short term, the impact of the economic slowdown on the labour market has been largely offset by massive public support measures, including the extension of the system of temporary unemployment and financial support for the self-employed. Nevertheless, around 100 000 jobs will be lost by the fall of 2021. Unemployment is rising, but the damage is still generally limited in relation to the size of the shock to GDP.

Core inflation should increase very little, from 1.3 % this year to 1.7 % in 2023. Rising wage costs, as well as the extra costs incurred in order to safely resume business activity, are generating inflationary pressure. Admittedly, the increase should remain small: profit margins will not fully recover. Headline inflation should rise more strongly, from 0.4 % in 2020 to 1.9 % in 2023, but that is mainly due to the unusually low level recorded this year, as a result of the sharp fall in oil prices. Rising inflation is in turn fuelling labour cost dynamics, which, through the wage indexation systems, are expected to rise relatively strongly over the projection period.

The budget deficit widens considerably, to reach 10.6 % of GDP in 2020, not only as a result of the economic crisis which automatically leads to more expenditure and less revenue, but also due to the wide-ranging support measures. As these are primarily of a temporary nature, the deficit should come down again in the next couple of years, even though it is still expected to be around 6 % of GDP. The government debt ratio expressed as a share of GDP is set to climb to around 120 % in 2023 and, with normal growth rates and a constant budget deficit, it is expected to remain on an upward path afterwards. This unsustainable budget position implies that any further economic recovery measures will have to be temporary and targeted at sound businesses and the most vulnerable groups. For the economic recovery to be sustainable, a step-by-step plan to consolidate public finances is required.